How Sekhon Family Office ( SFO ) Is Helping Nations Build Wealth By Free Markets Based Transformative Governance Models

- We work with bold, ambitious leaders who are not satisfied with the status quo and eager for change to address the key strategic governance tools that improve performance and help governments, public-sector, private-sector entities and larger society do the work they do better.

SFO PURPOSE — Doubling GDP of Continents, Countries, Businesses & Households.

Ranks of GDP in US$Trillion for Year 2021

0. World 91.03

1. Asia 34.39

2. North America 24.88

3. Europe 23.05

4. South America 2.90

5. Africa 2.49

6. Oceania 1.69

7. Antarctica N/A*

SFO Works With — Our Strong & PowerFul Network

- Global Bodies like WEF, UN, World Bank, IMF and their likes.

- Continent Representative / Trade Bodies like WTO, OECD and their likes.

- Country Governments

- County Trade Commissioners, Embassies etc.

- State Governments

- Municipalities

- Family Offices

- All sources of capital like Biggest Sovereign Funds, Private Equity Funds, Growth Funds, Hedge Funds, Stock Exchanges and Credit Institutions.

SFO LISTS — Ranks the world based on a variety of categories

- Premier Level

- Governor / CM Level

- Mayor Level

- County Level or Equivalent Level

- Ministry Level

- Entrepreneur Level

- Business Level

- Individual Level

SFO ECOSYSTEMS — To deliver Exponential Outcomes

- Free Markets Governance

- Balanced Score Card based Action Cycle Management

- Sustainability/GRI based Sustainable Development

- Exponential Technology Driven Growth

- MeaningFul Impact driven CSR/Foundation/Wellness

We make Governance Performance Based and Accountable

- Government spending now represents about 20 percent of the $90 trillion total global economy. We work with national and regional governments, city municipalities, quasi-government agencies such as development funds, trade associations, sovereign funds as well as government-owned companies to realize their economic and social goals.

- We support governments, business and society in building resilience to today’s challenges while undertaking the transformations necessary to deliver on the Common Future.

- For us, belief is the only metric that matters. We do not make business relationships for wowing our stakeholder with incredible numbers because numbers are really just an algorithm for passion and values. When passionate people move, world’s problems get solved. Passionate people only Think Future and Build it because That’s Where We Shall Spend The Rest Of Our Lives.

Three things that have lifted the human cause & economic activity most in the last three industrial revolutions and are a strong foundation that we help build for our customers are

- _Communications https://bit.ly/3ua9CM6_

- _Mobility https://bit.ly/37p8rhT_

- _Energy/Power _https://bit.ly/3u9l0rx_

- These three fundamentally change the way society manages, powers, and moves economic activity and hence supercharges the aggregate efficiency across supply chains and nations.

- Aggregate efficiency is the ratio of potential work to the actual useful work that gets embedded into a product or service. The higher the aggregate efficiency of a good or service, the less waste is produced in every single conversion in its journey across the value chain. The 3rd industrial revolution based infrastructure is failing the aggregate efficiencies of all economies. The healthcare infrastructure failed the world during pandemics. Japan had the maximum aggregate efficiency when it peaked out at 22.8 %. Still 87.2 % to be realized._

- Are you passionate ? Are you the voice for our values ? If yes join us to Build Back Better. Spread awareness and stay safe*

The public sector’s influence comes directly, through government entities, state-owned enterprises and institutional funding, as well as indirectly, through regulation and oversight. The sector is facing major challenges, such as rising costs, growing deficits, shifting centers of economic activity, a burgeoning war for talent and increasingly demanding customers.

- Public sector organizations are under pressure to deliver more for their citizens, from seamless digital services to policies and programs that address complex problems, societal challenges, and crises. We help the public sector improve how it operates so that it can meet, and surpass, these expectations and their goals.

- Recently, the use of stimulus funds and regulatory reform has further blurred the lines between public and private entities.

- We work with bold, ambitious leaders who are not satisfied with the status quo and eager for change to address the key strategic tools that improve performance and help public-sector entities do the work they do better.

Our experience serving public-sector clients encompasses the following areas, to name a few:

- Economic development and sector strategies

- Privatization

- Change management

- Cost and service-quality improvements

- Organizational design

- IT infrastructure

Transforming Public / Social Sector Organizations

- At a time when providing better outcomes for citizens means being responsive, agile, and able to devise creative solutions to complex problems, many public sector organizations remain hierarchical and bureaucratic. They’re built for another era. To perform on all fronts — from providing basic services to citizens to solving the most pressing societal challenges and responding to crises — governments need to transform how they’re organized and how they operate.

- Public and social sector organizations are key to societal and economic progress and well being. We work with social sector and government organizations to deliver Change that Matters to citizens, driving transformations that have a significant, positive impact on society. By combining a highly collaborative working model with insights from our globally recognized research centers, we provide an approach tailored to each client’s needs.

- Our work spans multiple sectors and functions, including digital and analytics, operations, organization, and strategy. We work end-to-end — from diagnosis to delivery of lasting impact — together generating tangible results that are improving the lives of millions worldwide.

- Our Government & Public Services is committed to improving public outcomes through a focus on people. We think about the complex issues facing the public sector and develop relevant, timely, and sustainable solutions for our clients.

- Developed and emerging economies are witnessing myriad challenges, ranging from climate change and accelerated urbanisation to resource scarcity. Apart from these challenges, the world is witnessing a shift in global economic power as well as a mix of demographic and social changes. This is driving economies to explore innovative solutions that also conform to the traditional set-ups and governance structures. We help governments and public sector organisations enable efficient governance practices infused with ingenuity and aided by technology.

Why Do We Need To Reinvent Governments & Global Governance

CHAPTER 1 — Human Freedom Of Speech and Liberty Under Attack with the current government systems .

- The gradual erosion of one of our most precious fundamental rights — the inalienable right to freedom of speech and expression — is leading to the gradual destruction of our human right to dissent and protest.

- This lethal cocktail is adversely impacting the liberty of all those who dare to speak up. Articles of our constitution, the right to life and personal liberty, is under a silent threat and we all know the consequence of losing our liberty. Simply put, we will cease to be a democratic republic. Of course, our fundamental rights cannot be absolute and so the constitution has placed a few reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right to free speech and these include restrictions placed in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, contempt of court, defamation and incitement to an offence.

- Yet, it is important to note that these restrictions can be imposed only by law enacted by parliament and the restrictions have to be reasonable.

- Today, freedom of speech is being eroded and mauled through twisting and turning the law if not abusing it altogether. The law needs to be objectively interpreted but subjective satisfaction has taken over and the consequences are unpalatable: dissent or expression of a different point of view has become an issue to the extent that bona fide speech sometimes becomes a security threat.

- Some cynics glibly suggest that if the speaker is not guilty, he or she will be acquitted of the charges framed, but the fact of the matter is that detention as an under-trial is a gut-wrenching experience for anyone and particularly for a person whose cries of innocence fall on deaf ears. Such a person looks to the judiciary for protecting his or her freedom of speech and liberty but gets overwhelmed by the painfully slow justice delivery system.

CHAPTER 2 — The Transformative Power of Governments if done as they should be done with

- Government has an important role in helping direct and facilitate transitions to help overcome societal problems.

CHAPTER 3— History Of Government and Types of Government and Why Governments Fail

There are many different forms of government but really just eight apply to us today.

- Absolute Monarchy (absolutism)

- Limited Monarchy (Constitutional Monarchy)

- Representative Democracy.

- Direct democracy.

- Dictatorship.

- Oligarchy.

- Totalitarianism.

- Theocracy.

No two governments, past or present, are exactly the same.

- However, it is possible to examine the similarities and differences among political and economic systems and categorize different forms of government. One simple way to categorize governments is to divide them into democratic and authoritarian political systems.

CHAPTER 4— What is Democracy ? Why Democracy ?

Democracies

- Many countries today claim to be democracies, but if the citizens are not involved in government and politics, they are democratic in name only. Some governments are more democratic than others, but systems cannot be considered truly democratic unless the meet certain criteria:

Whither democracy? It was not until 1920 — after decades of tireless protest and campaigning — that women were granted suffrage by the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

- Freedom of speech, the press, and religion. Democracies in general respect these basic individual liberties. No government allows absolute freedom, but democracies do not heavily censor newspapers and public expression of opinions.

- Majority rule with minority rights. In democracies, people usually accept decisions made by the majority of voters in a free election. However, democracies try to avoid the “tyranny of the majority” by providing ways for minorities all kinds to have their voices heard as well.

- Varied personal backgrounds of political leaders. Democracies usually leave room for many different types of citizens to compete for leadership positions. In other words, presidents and legislators do not all come from a few elite families, the same part of the country, or the same social class.

- Free, competitive elections. The presence of elections alone is not enough to call a country a democracy. The elections must be fair and competitive, and the government or political leaders cannot control the results. Voters must have real choices among candidates who run for public office.

- Rule by law. Democracies are not controlled by the whims of a leader, but they are governed by laws that apply to leaders and citizens equally.

- Meaningful political participation by citizens. By itself, a citizen’s right to vote is not a good measure of democracy. The government must respond in some way to citizen demands. If they vote, the candidate they choose must actually take office. If they contact government in other ways — writing, protesting, phoning — officials must respond.

- The degree to which a government fulfills these criteria is the degree to which it can be considered democratic. Examples of such governments include Great Britain, France, Japan, and the United States.

Will Democracy Stay Democratic In A Digitally Borderless World

What is democracy?

- Democracy these days is more commonly defined in negative terms, as freedom from arbitrary actions, the personality cult or the rule of a nomenklatura, than by reference to what it can achieve or the social forces behind it. What are we celebrating today? The downfall of authoritarian regimes or the triumph of democracy? And we think back and remember that popular movements which over threw anciens régimes have given rise to totalitarian regimes practising state terrorism.

- So we are initially attracted to a modest, purely liberal concept of democracy, defined negatively as a regime in which power cannot be taken or held against the will of the majority. Is it not enough of an achievement to rid the planet of all regimes not based on the free choice of government by the governed? Is this cautious concept not also the most valid, since it runs counter both to absolute power based on tradition and divine right, and also to the voluntarism that appeals to the people’s interests and rights and then, in the name of its liberation and independence, imposes on it military or ideological mobilization leading to the repression of all forms of opposition?

- This negative concept of democracy and freedom, expounded notably by Isaiah Berlin and Karl Popper, is convincing because the main thing today is to free individuals and groups from the stifling control of a governing élite speaking on behalf of the people and the nation. It is now impossible to defend an antiliberal concept of democracy, and there is no longer any doubt that the so-called “people’s democracies” were dictatorships imposed on peoples by political leaders relying on foreign armies. Democracy is a matter of the free choice of government, not the pursuit of “popular” policies.

- In the light of these truths, which recent events have made self-evident, the following question must be asked. Freedom of political choice is a prerequisite of democracy, but is it the only one? Is democracy merely a matter of procedure? In other words, can it be defined without reference to its ends, that is to the relationships it creates between individuals and groups? At a time when so many authoritarian regimes are collapsing, we also need to examine the content of democracy although the most urgent task is to bear in mind that democracy cannot exist without freedom of political choice.

The collapse of the revolutionary illusion

- Revolutions sweep away an old order: they do not create democracy. We have now emerged from the era of revolutions, because the world is no longer dominated by tradition and religion, and because order has been largely replaced by movement. We suffer more from the evils of modernity than from those of tradition. Liberation from the past interests us less and less; we are more and more concerned about the growing totalitarian power of the new modernizers. The worst disasters and the greatest injury to human rights now stem not from conservative despotism but from modernizing totalitarianism.

- We used to think that social and national revolutions were necessary prerequisites for the birth of new democracies, which would be social and cultural as well as political. This idea has become unacceptable. The end of our century is dominated by the collapse of the revolutionary illusion, both in the late capitalist countries and in the former colonies.

- But if revolutions move in a direction diametrically opposed to that of democracy, this does not mean that democracy and liberalism necessarily go together. Democracy is as far removed from liberalism as it is from revolution, for both liberal and revolutionary regimes, despite their differences, have one principle in common: they both justify political action because it is consistent with natural logic.

- Revolutionaries want to free social and national energies from the shackles of the capitalist profit motive and of colonial rule. Liberals call for the rational pursuit of interests and satisfaction of needs. The parallel goes even further. Revolutionary regimes subject the people to “scientific” decisions by avant-garde intellectuals, while liberal regimes subject it to the power of entrepreneurs and of the “enlightened” classes the only ones capable of rational behaviour, as the French statesman Guizot thought in the nineteenth century.

- But there is a crucial difference between these two types of regime. The revolutionary approach leads to the establishment of an all-powerful central authority controlling all aspects of social life. The liberal approach, on the other hand, hastens the functional differentiation of the various areas of life politics, religion, economics, private life and art. This reduces rigidity and allows social and political conflict to develop which soon restricts the power of the economic giants.

- But the weakness of the liberal approach is that by yoking together economic modernization and political liberalism it restricts democracy to the richest, most advanced and best-educated nations. In other words, elitism in the international sphere parallels social elitism in the national sphere. This tends to give a governing elite of middle-class adult men in Europe and America enormous power over the rest of the world over women, children and workers at home, as well as over colonies or dependent territories.

- One effect of the expanding power of the world’s economic centres is to propagate the spirit of free enterprise, commercial consumption and political freedom. Another is a growing split within the world’s population between the central and the peripheral sectors the latter being not that of the subject peoples but of outcasts and marginals. Capital, resources, people and ideas migrate from the periphery and find better employment in the central sector.

- The liberal system does not automatically, or naturally, become democratic as a result of redistribution of wealth and a constantly rising standard of general social participation. Instead, it works like a steam engine, by virtue of a big difference in potential between a hot pole and a cold pole. While the idea of class war, often disregarded nowadays, no longer applies to post-revolutionary societies, it still holds good as a description of aspects of liberal society that are so basic that the latter cannot be equated with democracy.

The twilight of social democracy

- This analysis is in apparent contradiction with the fact that social democracy developed in the most capitalist countries, where there was a considerable redistribution of income as a result of intervention by the state, which appropriated almost half the national income and in some cases, especially in the Scandinavian countries, even more.

- The main strength of the social democratic idea stems from the link it has forged between democracy and social conflict, which makes the working-class movement the main drivingforce in building a democracy, both social and political. This shows that there can be no democracy unless the greatest number subscribes to the central principles of a society and culture but also no democracy without fundamental social conflicts.

- What distinguishes the democratic position from both the revolutionary and the liberal position is that it combines these two principles. But the social democratic variant of these principles is now growing weaker, partly because the central societies are emerging from industrial society and entering post-industrial society or a society without a dominant model, and partly because we are now witnessing the triumph of the international market and the weakening of state intervention, even in Europe.

- So Swedish social democracy, and most parties modelled on social democracy, arc anxiously wondering what can survive of the policies constructed in the middle of the century. In some countries the trade union movement has lost much of its strength and many of its members. This is particularly true in France, the United States and Spain, but also in the United Kingdom to say nothing of the excommunist countries, where trade unions long ago ceased to be an independent social force. In nearly all countries trade unionism is moving out of the industrial workplace and turning into neocorporatism, a mechanism for protecting particular professional interests within the machinery of the state: and this leads to a backlash in the form of wild-cat strikes and the spread of parallel ad hoc organizations.

- So we come to the most topical question about democracy: if it presupposes both participation and conflict, but if its social-democratic version is played out, what place does it occupy today? What is the specific nature of democratic action, and what is the “positive” content of democracy? In answering these questions we must first reject any single principle: we must equate human freedom neither with the universalism of pragmatic reason (and hence of interest) nor with the culture of a community. Democracy can neither be solely liberal nor completely popular.

- Unlike revolutionary historicism and liberal utilitarianism, democratic thinking today starts from the overt and insurmountable conflict between the two faces of modern society. On the one hand is the liberal face of a continually changing society, whose efficiency is based on the maximization of trade, and on the circulation of money, power, and information. On the other is the opposing image, that of a human being who resists market forces by appealing to subjectivity the latter meaning both a desire for individual freedom and also a response to tradition, to a collective memory. A society free to arbitrate between these two conflicting demands that of the free market and that of individual and collective humanity, that of money and that of identity may be termed democratic.

- The main difference as compared with the previous stage, that of social democracy and the industrial society, is that the terms used are much further apart than before. We are now concerned not with employers and wage-earners, associated in a working relationship, but with subjectivity and the circulation of symbolic goods.

- These terms may seem abstract, but they are no more so than employers and wage-earners. They denote everyday experiences for most people in the central societies, who are aware that they live in a consumer society at the same time as in a subjective world. But it is true that these conflicting facets of people’s lives have not so far found organized political expression just as it took almost a century for the political categories inherited from the French Revolution to be superseded by the class categories specific to industrial society. It is this political time-lag that so often compels us to make do with a negative definition of democracy.

Arbitration

- Democracy is neither purely participatory nor purely liberal. It above all entails arbitrating, and this implies recognition of a central conflict between tendencies as dissimilar as investment and participation, or communication and subjectivity. This concept can be adapted to the most affluent post-industrializing countries and to those which dominate the world system; but does it also apply to the rest of the world, to the great majority of the planet?

- A negative reply would almost completely invalidate the foregoing argument. But in Third World countries today arbitration must first and foremost find a way between exposure to world markets (essential because it determines competitiveness) and the protection of a personal and collective identity from being devalued or becoming an arbitrary ideological construct.

- Let us take the example of the Latin American countries, most of which fall into the category of intermediate countries. They are fighting hard and often successfully to regain and then increase the share of world trade they once possessed. They participate in mass culture through consumer goods, television programmes, production techniques and educational programmes. But at the same time they are reacting against a crippling absorption into the world economic, political and cultural system which is making them increasingly dependent. They are trying to be both universalist and particularist, both modern and faithful to their history and culture.

- Unless politics manages to organize arbitration between modernity and identity, it cannot fulfil the first prerequisite of democracy, namely to be representative. The result is a dangerous rift between grass-roots movements seeking to defend the individuality of communities, and political parties, which are no more than coalitions formed to achieve power by supporting a candidate.

- The main difference between the central countries and the peripheral ones is that in the former a person is defined primarily in terms of personal freedom, but also as a consumer, whereas in the latter the defence of collective identity may still be more important, to the extent that there is pressure from abroad to impose some kind of bloodless revolution in the form of compulsory modernization on the pattern of other countries.

- This conception of democracy as a process of arbitration between conflicting components of social life involves something more than the idea of majority government. It implies above all recognition of one component by another, and of each component by all the others, and hence an awareness both of the similarities and the differences between them. It is this that most sharply distinguishes the “arbitral” concept from the popular or revolutionary view of democracy, which so often carries with it the idea of eliminating minorities or categories opposed to what is seen as progress.

- In many parts of the world today there is open warfare between a kind of economic modernization which disrupts the fabric of society, and attachment to beliefs. Democracy cannot exist so long as modernization and identity are regarded as contradictory in this way. Democracy rests not only on a balance or compromise between different forces, but also on their partial integration. Those for whom progress means making a clean sweep of the past and of tradition are just as much the enemies of democracy as those who see modernization as the work of the devil. A society can only be democratic if it recognizes both its unity and its internal conflicts.

- Hence the crucial importance, in a democratic society, of the law and the idea of justice, defined as the greatest possible degree of compatibility between the interests involved. The prime criterion of justice is the greatest possible freedom for the greatest possible number of actors. The aim of a democratic society is to produce and to. respect the greatest possible amount of diversity, with the participation of the greatest possible number in the institutions and products of the community.

CHAPTER 5— What is Authoritarian Regimes ? Why Authoritarian Regimes should not exist?

Authoritarian Regimes

- Mao Zedong’s position as authoritarian ruler of the People’s Republic of China is glorified in this propaganda poster from the Cultural Revolution. The poster reads: “The light of Mao Zedong Thought illuminates the path of the Great Cultural Revolution of the Proletariat.”

- One ruler or a small group of leaders have the real power in authoritarian political systems. Authoritarian governments may hold elections and they may have contact with their citizens, but citizens do not have any voice in how they are ruled. Their leaders do not give their subjects free choice. Instead, they decide what the people can or cannot have. Citizens, then, are subjects who must obey, and not participants in government decisions. Kings, military leaders, emperors, a small group of aristocrats, dictators, and even presidents or prime ministers may rule authoritarian governments. The leader’s title does not automatically indicate a particular type of government.

- Authoritarian systems do not allow freedoms of speech, press, and religion, and they do not follow majority rule nor protect minority rights. Their leaders often come from one small group, such as top military officials, or from a small group of aristocratic families. Examples of such regimes include China, Myanmar, Cuba, and Iran.

- No nation falls entirely into either category. It also dangerous to categorize a nation simply by the moment in time during which they were examined. The Russia of 1992 was very different from the Russia of 1990. Both democratic and authoritarian governments change over time, rendering the global mosaic uncertain and complex.

CHAPTER 6 — WHETHER DEMOCRACY OR AUTHORITARIAN REGIMES IS BETTER FOR FUTURE

Democracy vs. Authoritarianism

- The word democracy comes from the Greek words ‘demos,’ which refers to the people, and ‘kratos,’ which means power. Thus, a democratic state is one in which power emanates from the people. One might say, then, that authoritarianism is the opposite of a democracy. In an authoritarian regime, all power is concentrated in one person alone, often referred to as the dictator.

- Lets investigate the specific aspects of democracy and authoritarianism which clarify how these two systems of power and governance diverge, especially in terms of the effects these systems have on the citizens of the nation, and in terms of what each system likewise demands of its citizens.

- As we deepen our reflection on Martial Law as a period in Philippine history, we also deepen our imagination of how Filipinos during Martial Law must have thought and felt about their situation, and what eventually drove them to choose democracy over authoritarianism on EDSA, and rise up as one to make that difference.

- One of the most basic features of a democracy that sets it apart from authoritarianism is the process by which leaders are chosen. Because democracy is meant to uphold the power of the people, leaders are chosen such that they truly represent the people’s interests. This is done through fair and honest elections, whereby citizens may collectively express their choice of leaders through the ballot.

Leaders are thus chosen based on whom the electorate collectively selects, and the power of the leader stems from this mandate. To ensure the integrity of elections, they are administered by a neutral party, with independent observers for the voting and counting processes, and citizens must be able to vote in confidence, without intimidation or fear of violence. An election governed by citizens’ choice is designed so that elected representatives are those who truly listen to their people and aim to address their needs. Held at regular intervals, elections furthermore ensure that those in power cannot extend their term without the consent of the people.

In an authoritarian state, such mechanisms are rendered either obsolete or futile. Dictators want to cling to power, and so the very notion of an election is counter to that desire. Thus, authoritarian states often do away with elections entirely, taking the choice away from the people to begin with. In more insidious cases, dictators engage the electoral process but dishonestly. By rigging the system, while offering their citizens the illusion of choice, the staged elections only serve to legitimize the dictator’s continued rule, as it continues to seem as if the dictator enjoys the support of the public.

CIVIC PARTICIPATION

Beyond the selection of leaders, another feature that differentiates democracies from authoritarian states is the level of civic participation that is expected and allowed. Democracies favor, and in fact thrive on, the active participation of its citizens in the political landscape, whereas dictators quash even the possibility of genuine participation.

In democracies, citizens are encouraged to participate by being informed about public issues, and freely expressing their opinions on these issues, as well as the decisions of their elected representatives. Citizens are likewise given the power to shape these decisions by being active members of civil society and non-government organizations. Even on the level of voting wisely in elections, and thereby choosing what interests should be prioritized in governance, citizens may actively participate in the exercise of power. Across these means of participation, citizens are enjoined to participate peacefully, respectfully toward the law, and with sensitivity to the plurality of views that exist in society.

Authoritarian states reject these modes of participation; and indeed, participation in principle. Public dissent is deemed public rebellion, a threat to the dictator’s unopposed tenure in power, and dictators inflict state violence to silence such opposition. Meanwhile, decision-making is limited to the dictator’s wishes as well, such that they may enact laws and decrees for the benefit of his own interest without appropriate mechanisms to keep their actions in check — no laws to limit them, no plurality to take into consideration.

FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES

Finally, what sets democracies apart from authoritarianism is their treatment of fundamental liberties. Truly democratic societies are those which respect and uphold the fundamental liberties of all their citizens, regardless of who they are. These liberties include the basic freedoms of expression, religion, assembly, and the press, as well as basic rights such as the right to privacy, to due process, and to life.

A dictator, on the other hand, does not respect these freedoms and rights. This is because these freedoms and rights typically make the dictator vulnerable to criticism, to the exposure of their abuses, and ultimately to the limits of their power. Because our fundamental liberties apply equally to all, they must apply equally to the dictator and ordinary citizens, whoever they may be. A dictator, therefore, often ignores or even violates these rights, to perpetuate themselves in power. So long as they can convince the populace that they are more important than everyone else, and subject to a different standard, they allow themselves that much more room to act with impunity.

Our study of the differences between democracy and authoritarianism really comes down to one question: What kind of society do you want to live in? As the exhibit above has shown, the design of a society shapes how power is obtained and exercised, and in doing so, likewise shapes the way in which citizens may live in freedom, harmony, and dignity.

But what follows from this question is perhaps even more important: What can you do to shape the society you want to live in? How can we live as engaged citizens, given the structure and order of our present society — and what can we do to make it better?

CHAPTER 7— What is Global Governance ? Why Global Governance ?

Plato was right: we need more scientists at the heart of global governance

In the famous Dialogues of Plato one of the central themes in the essay “Republic” is the discussion on who may lead the community with the philosopher advanced as the rightful type of individual for leadership.

More than two thousand years later the question appears to be as relevant as ever, not just at the level of municipalities or countries, but also for the global community.

The global governance system needs not only new layers of governance, but also a greater role to be performed by the scientific community within the governing structures of global institutions.

Back in 2001 a United Nations Development Programme report looked at the issue of global governance and concluded: “we derive a subsidiary argument that the failure to outfit technology to the needs of the poor countries is largely a result of the current inadequacies in the global governance system to guide the process of technological change.”

Since then, the rapid tempo of technological progress was accompanied by significant gaps and inequalities in economic and technological development across countries, with the evolving system of global governance characterized by weakening of global institutions becoming less effective in the face of global challenges.

The current system of global governance is largely anchored in geography, with the key layers represented by the level of countries, regions (a level that is not fully integrated into the global economic architecture) and the global level of international organizations, whose membership is rooted in national and regional constituencies.

The centrality of the nation state in the global architecture renders the whole construct more vulnerable to bouts of instability emanating from the excesses of Realpolitik and zero-sum tactics prevailing over longer term cooperative strategies.

One of the possible ways of stabilizing and depoliticizing the edifice of the global economy is to create a layer of global governance that focusses on technological development and that is governed to a greater degree by the leading representatives of the scientific and technological community rather than politicians.

Importantly there are steps already undertaken at the international level to strengthen the coordination of technological development across countries.

One important initiative coming from the World Economic Forum is to create Global Councils to restore trust in technology, with the following key priorities on the agenda:

Six councils formed to design how emerging technology can be governed for the benefit of society, Top decision-makers and experts from the public and private sectors, civil society and academia participate in inaugural Global Fourth Industrial Revolution Council meeting in San FranciscoLeaders of Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Dana-Farber, European Commission, Microsoft, Qualcomm, Uber, World Bank among chairsMajor global summit on technology governance announced, to take place in April 2020

Some of the other measures undertaken at the level of international organizations to address the technological gap include a UN-sponsored initiative to create a Technology Bank for least developed countries.

The Technology Bank began its operations in September 2017 with the signing of the host country agreement between the United Nations and Turkey According to the UN, the objective of the Bank “is to support LDCs [least developed countries] in building their STI capacity; foster national and regional innovation ecosystems; support homegrown research and development; facilitate market access; build capacity in the areas of intellectual property rights; and assist with the transfer of appropriate technologies “.

The key priority in the evolving set of global initiatives in the technological sphere will need to be focused on the assistance accorded to the least developed economies in bridging their technology gap.

Some of the other issues that may become part of the of the global technology agenda include:

- Cyber-security

- Coordination with international organizationsCoordination with international organizations

- Educational cooperation

- Propagation of new technologies

- Environmental technologies to face the challenges of global warming

- Monitoring of technological advances and global technological vulnerabilities/disruptions

With the creation of a technological layer, the global governance construct may become more conducive to addressing the world-wide problems such as cross-country technological gaps or rising vulnerabilities to technological disruptions.

It may also broaden the dimensions of international cooperation, which in current conditions appear to be circumscribed largely to bilateral, i.e. country-to-country channels, with the levels of cooperation at the regional level and international organizations relegated to lower importance.

The emerging technological layer of global governance needs to be not separate but intertwined with other layers of global governance.

In effect, the technological layer of global economic architecture may create the fourth dimension in global governance (in addition to country-level, regional and global institutions) that broadens the time-horizons and reduces the global economy’s susceptibility to the excesses of countries’ narrow self-interest.

The exact contours of a new layer of technological governance in the global economy are yet to be defined, but a key role in this formation may be played by international technological and scientific networks, including alliances formed by leading universities.

The emerging technological layer of global governance needs to be not separate but intertwined with other layers of global governance. The linkages need to be developed with the international institutions such as the WTO (on issues such as intellectual property rights), IMF, World Bank (transfer of technology to the poorest countries) as well as the regional development institutions.

There is also an important “human capital” dimension to the formation of a technological layer of global governance as this allows the scientific and technological community to have more of a say on global issues.

Indeed, the mounting problems in global development may be at least in part due to the excessive leverage of politicians at various levels of global governance. A revamped system of global governance needs to allow for a more depoliticized structure with a greater representation accorded to the scientific community.

The disheartening results of the past several decades of a politically driven governance system characterized by intensifying global risks do suggest that Plato’s advocacy of community leadership being assumed by philosophers (i.e. scientists in the modern sense), may turn out to be topical after all.

Gaps in global governance are holding back the world’s economy. Here’s how

Since the mid-20th century the world’s economic architecture has largely been taken for granted, partly due to the rising role of developed economies and the mounting impulses of economic openness promoted by international institutions.

Throughout the past decade, however, the current system of governance in the world economy started to encounter systemic bottlenecks and limitations as exemplified by rising inequality as well as declining economic growth rates. These developments call into question the seamlessness and finality of the current construct of global economic architecture. The question that arises then is whether the current system is economically efficient and what steps could be undertaken to bring the governance framework more into line with the challenges posed by changing conditions in the world economy.

In fact, signs of a systemic malfunction in the global governance framework go beyond the standard references to global imbalances, inequality and the “new normal” of slower growth rates for longer. No less worrisome are the gaps associated with the lack of capacity to deal with environmental and technological challenges as well as declining productivity momentum. Another issue is the lack of efficiency in the use of resources as pointed out in a recent research paper by Milligan et al (2018), with authors calling for regional agreements to play a greater role in bridging global governance gaps.

Have you read?

- Plato was right: we need more scientists at the heart of global governance

- How leaders can use ‘agile governance’ to drive tech and win trust

- We need a new framework for global governance. Here’s how we could build one

According to Milligan et al (2018), “major gaps remain in cooperative resource management across spatial jurisdictional boundaries at national, regional and international scales. These gaps contribute to: inefficient use of land (UNEP, 2014a), water (UNEP, 2012b) and various other resources; transboundary pollution (Lee et al., 2016); uncoordinated regulation by governments of transnational actors; and tensions and conflict associated with competing or conflicting claims to resources (UNFT, 2012, Schofield, 2012). An illustrative example of scale of resource cooperation challenges is that 158 of the world’s 263 transboundary water basins lack any type of cooperative management framework (WWAP, 2015)”

Another illustration of the breakdown of the current system is of course the propagation of protectionism, bilateralism and the weakening of global multilateral institutions such as the WTO. There are also notable omissions in governance with respect to the lack of integration of regional institutions into the global governance framework, which significantly limits the capability of the world economy to launch new liberalization initiatives or coordinated spending to prop up global growth. The lack of integration of regionalism into the global governance framework leaves too much scope for national egoism and severely limits the ability of the world economy to deal with downturns in a coordinated and comprehensive manner.

Currency wars and protectionism

The problems of an inefficient global governance system are exacerbated by currency wars and rising protectionism as represented by large-scale export subsidies, import tariffs, as well as a plethora of other restrictive measures. This in turn has resulted in a prioritization of import-substitution and export-oriented sectors at the expense of greater spending on areas such as infrastructure or human capital development. During the high-level “Dialogue of continents” forum held in Hamburg in October this year the issue of the misallocation of resources in the global economy (partly as a result of excesses in industrial policy and protectionism) was discussed with respect to the possible explanations behind the deterioration in the global economy’s growth figures.

The broader problem for the global governance system whose structure largely still reflects the fundamentals of mid-20th century world economy is the emergence of new players that are either global or mega-regional in scale. The advent of mega-regional blocks (TPP-11, possible deal on RCEP, Africa’s continental free trade area) in the past several years will undoubtedly raise the pressure to change the current system towards a greater role for regional institutions.

Transnational corporations

Another challenge is the rising dominance of transnational corporations in the services and high-tech sectors, whose regulation thus far cannot be effectively implemented at national, regional or global levels. Whether a whole new technological governance layer in the world economy is needed to address the challenges of excessive market power, technological imbalances, cybersecurity, etc may be an issue to explore for policymakers in the coming years.

Even more broadly, what is the key priority for the world community in revamping the global economic architecture? Should economic efficiency be the overriding guide or should the global community be more concerned about the direction of equity, sustainability, inclusiveness and other indications of the “global moral compass”? The truth of the matter is that the current framework has problems on both counts — both efficiency and sustainability indicators demonstrate substantial gaps. In view of the critically high levels of inequality, of greater importance at this juncture may be the prioritization of lowering imbalances across countries and regions — the UN Development goals, most notably those pertaining to human capital development, need to be accorded greater weight.

There is a sizeable gap between developed and developing nations not only in terms of income levels, but also the scale of involvement in integration projects across the globe

In this regard, perhaps the most acute problems in terms of sustainability and inclusiveness of global economic development relate to the imbalances and inequalities along the North-South axis that are not only persistent, but widening. In terms of governance, existing multilateral institutions have proven to be slow in adjusting member country weights in voting structure to the significant increase in the share of some of the developing countries in the world economy. There is also the sizeable gap between developed and developing nations not only in terms of income levels, but also the scale of involvement in integration projects across the globe. The exponential growth in technological development, including AI, may exacerbate the technological and development gaps between the North and the South.

In sum, the fundamentals of the world economy have changed tremendously in the past several decades and the “superstructure” of global governance needs to reflect these shifts. More frequently than not instead of pointed discussions on transforming global governance one observes a tacit longing for a return to the governance model that prevailed in the preceding several decades perhaps in the hope that the swings in the US electoral cycle could majestically reassemble the world order of the past. Such hopes of foregoing any changes in the global economic architecture are misplaced given the disconnect between the inertia of global governance and the acceleration in the technological and geo-economic transformation of the world economy. Rather than walking several decades back in time, the world’s governance framework needs to be at least in synch with the massive qualitative changes that have taken place since the 2008–2009 crisis.

Identifying inefficiencies

Reforming the global governance system needs to start with the diagnostics of inefficiencies as well as development and regulatory gaps. Most importantly we need a global governance framework that is capable to adjust and reform its operations in an inclusive manner with due regard to the constantly changing conditions and fundamentals in the world economy.

Such a framework is likely to emerge as the world economy becomes more multipolar and more balanced across the main regions. At the same time the evolving changes in global governance also need to ensure continuity with respect to the role of multilateral institutions, such as the UN, the IMF, the World Bank and the WTO. New elements that are created within the global economic architecture need to support these institutions and work jointly to promote a more stable and inclusive system of governance.

The Coming Crisis: why global governance doesn’t really work

Serious problems undermine the current regime and create a significant ‘global governance deficit’

Nobody can say that the major institutions of global governance haven’t noticed the possibility that a further global economic crisis might be brewing.

The World Bank warned in January this year that a ‘perfect storm’ could be building in the global political economy. It was worried by the potential combination of a simultaneous slowing of economic activity across the BRICs and what it euphemistically termed ‘financial market stress’. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) followed the same line. In a speech delivered in Germany in April, its Managing Director, Christine Lagarde, spoke of her fear that the global economy had lost its growth momentum and was stuck in the ‘new mediocre’. ‘We are on alert’, she said, but ‘not alarm’.

The most recent expression of anxiety came just a couple of weeks ago from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the Paris-based body which is becoming ever more important in shaping and delivering global economic governance. Its chief economist, Catherine Mann, introduced the publication of the OECD’s latest economic outlook by identifying the emergence of ‘a self-fulfilling low-growth trap’ over the past eight years since the crisis broke. The longer this remained the case, she observed, the more difficult it would be to break the ‘negative feedback loops’. The resulting risk was that a ‘negative shock could tip the world back into another deep downturn’.

So they’ve noticed — at least the technocrats of global governance have. The more pertinent question, however, is whether they have actually been able to do anything to head off a second crisis. This takes us to politics and politicians — in this case, the leaders of the countries that belong to the Group of 20(G20), the new overarching ‘steering committee’ of global economic governance set up in a hurry, almost a panic, in autumn 2008 to preside over and direct the global political economy.

The G20 summit for 2016 will not take place until early September when leaders will gather in Hangzhou in China. But two meetings of the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors have met under the Chinese Presidency — in Shanghai in February and in Washington DC in April — and have produced two (almost identikit) communiqués of quite astonishing complacency. Sure, the ministers and governors acknowledged the uneven character of the modest growth that is currently being achieved, but, for the rest: well, they were committed to using all available policy tools (monetary, fiscal and structural); were indeed pressing on with structural reforms; had not taken their eye off Basel 111 and financial sector reform; and were still trying to get countries signed up to their Base Erosion and Profit Sharing project designed to foster a fairer international tax system.

The overall message was clear: things aren’t perfect in the global economy, but we know what we are doing, and we are in fact doing a lot to manage the system. There was no hint of the ‘coming crisis’ as explored in these SPERI blogs and scarcely any reference to what, tellingly, Martin Craig has called the ‘other crisis’. On this front the February meeting did no more than ‘welcome’ the Paris Agreement on Climate Change and the April meeting merely asked the G20 Green Finance Study Group to come up with some specific options.

So, what’s going on in global governance? Why can’t it do better? I identify at least three important problems that undermine the capacity of the current regime and create a significant ‘global governance deficit’ in the space in which we presently need imagination, substance and leadership.

The first problem has long been identified within the best academic accounts of the major global economic institutions (see the many invaluable publications of Jeffrey Chwieroth of the LSE). Although there has always been more internal disagreement within the major global economic institutions than some on the left have generally wanted to admit, the fact remains that the vast majority of the staff of the IMF and World Bank especially have been trained in the US economics mainstream. Even when they dissent, as in the recent suggestion by members of the IMF research department that neoliberalism might perhaps have been ‘oversold’, they tend not to stray very far from that mainstream.

What Lagarde, Mann and most global governance technocrats want is for the global economy, broadly as currently constituted, to work better than it is at the moment, to grow again and perhaps be put to the service of rather more people than was the case during the wild, expansionary years preceding the crisis. That is why they have been speaking out in the way they have been lately. But they don’t want or see the need for a different type of global political economy.

The second problem is that the structure of global governance assembled over the years since 1944 (amidst what Stephen Buzdugan and I describe as a ‘long battle’ over the nature and shape of global governance between contending groups of states) is actually very weak. The IMF and the World Bank have very little direct power over countries unless and until a country runs into economic problems and need outside financial help. At this point, ‘conditionalities’ kick in and the powers of the two agencies are booted up.

Most of the time, all the institutions can do is seek to adjust the climate of opinion within which key global political leaders act (by, for example, issuing warnings). It is, in the end, their weakness, rather than their strength, which is their most striking feature.

By contrast, the G20 states do have the power to act. Their economies make up the bulk of the global economy. They can deploy a fuller range of economic powers, stop squeezing life out of their economies and begin to address the interface between renewed economic growth and the climate. It’s just that they don’t! Admittedly, building any global governance institution is a hard task and, as I have argued previously, the G20 as an organisation is deficient in design and has consequently disappointed in performance over the last few summits.

But that’s not really the core explanation of the failure of world leaders to grapple imaginatively with the prospect of a further economic and financial crisis that then becomes entwined with an ecological crisis. The key point is that the G20 is still dominated politically by a wedge of G7 neoliberal states. Other countries with different political positions and traditions remain — for the moment at least — unwilling to tangle with them too openly within the structures of global governance. As a result, the G20 has stalled as a political agency capable of directing the global economic institutions.

Finally, there is a third problem and maybe it’s the biggest problem of all. It’s also never talked about. The truth is that the leaders of the neoliberal states don’t want effective global governance. Why not? Because effective global governance would be public governance, would guide and regulate, would insist on controlling the wilder excesses of finance and capitalism generally, would seek to steer the global economy. It would, in a phrase, be social democratic in character. It could not be otherwise, given what needs to be done. However, the leaders of the countries that still dominate global governance don’t want this type of global governance. They acknowledge the need for there to exist understood ‘rules of the game’ in finance, investment and trade, but they much prefer the privatised, corporate, style of global governance that, for example, the proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership offers.

In a nutshell, global governance can only be what the most powerful countries in the world allow it to be — and this may not be enough to avert a further crisis.

We need a new framework for global governance. Here’s how we could build one

The current global governance system is in flux as the centrality of global institutions is weakened, and nation states are reasserting their powers.

At the same time the in-between layer of global governance (between global institutions and nation states), namely regional integration arrangements, is undergoing massive changes: apart from the formation of megaregional blocks and the sheer rise in numbers resulting in ‘disorganization’ (sometimes together with bilateral FTAs referred to as a ‘spaghetti bowl’ of alliances), the regional integration projects along the South–South axis are becoming the focal point of ‘alternative economic integration’ vis-à-vis the well-advanced integration system in the developed world.

It is this intermediate layer of regionalism that may become a more prominent factor in the economic and political contradictions of the future world economy and the overall instability of the changing global governance system.

Regional integration

There is, hence, a need to devise arrangements that may render greater stability in the global governance framework via coordination among regional institutions and integration arrangements.

In this regard, in the sphere of cooperation among regional development institutions, there may be a case for multilateral consortia of regional development banks to promote connectivity as well as the broader development goals.

A cooperative platform could bring together China’s development institutions as well as other development banks and funds from across the Eurasian continent.

In the case of the Belt and Road Initiative, such a cooperative platform could bring together China’s development institutions as well as other development banks and funds from across the Eurasian continent — what may be referred to as the Silk Road Development Consortium — that would seek to exploit the synergies in the cooperation of the existing Eurasian institutions along the Silk Road route, ranging from the European Investment Bank in the West to China Development Bank and the China–ASEAN Investment Cooperation Fund in the East.

The benefits could include possibilities for co-financing projects in the respective parts of Eurasia, the possibility to share expertise in infrastructure development, greater ability to develop longer-term strategies on common project pipelines, as well as the enhanced possibility to complement rather than contradict or duplicate each other’s efforts in the Eurasian space.

Belt and Road model

Taking this a step further, the Eurasian connectivity projects like the BRI could be replicated in other continents — Africa or South America, where the lack of infrastructure development and regional connectivity is stifling growth.

In Africa the continental consortium of development institutions could include the respective regional development banks such as the Development Bank of South Africa, the African Development Bank, etc.

A similar continental platform could be created in South America to include the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB), Mercosur Structural Convergence Fund (Fondo para la Convergencia Estructural del MERCOSUR), Development Bank of Latin America (CAF) and other development institutions.

Even more broadly, there may be a case for a global coordination mechanism among the largest regional integration arrangements from both the North and the South. Such a framework could operate separately on the basis of coordination among the respective regional development institutions, or it could be coordinated via global networks and organizations such as the G20 or the WTO.

The G20 could be the best forum to launch discussions on such a platform and/or on broader issues of coordination among regional integration arrangements, given that it brings together the largest developing and developed economies that in turn are leading powers in their respective regions/continents, and that frequently head the formation of a regional economic block.

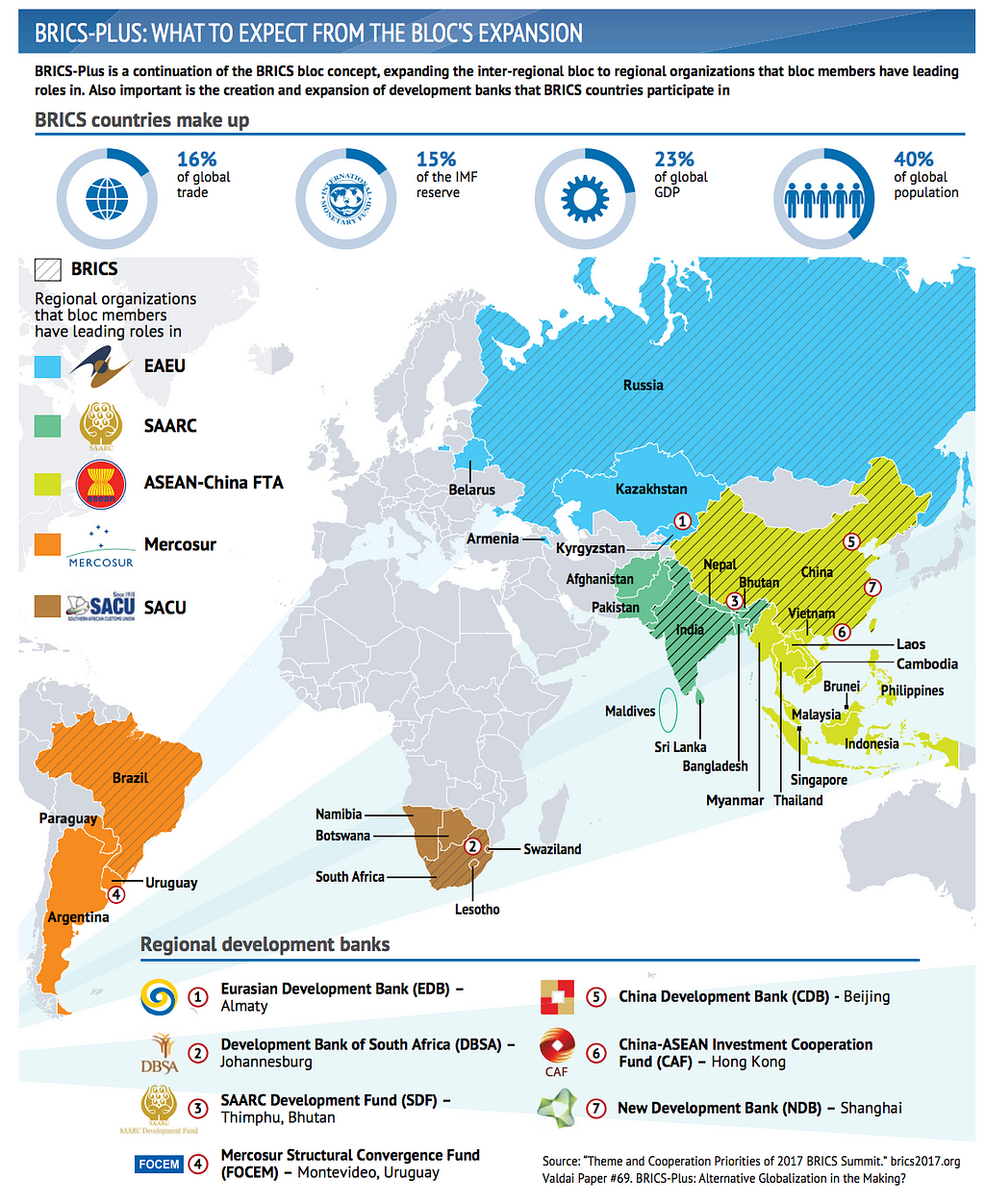

The list of some of the largest regional integration arrangements in such a framework could include NAFTA and the EU, as well as MERCOSUR, EAEU and RCEP (once it is formed to include China and ASEAN countries).

In summary, what is missing in the current system of global governance is greater coordination among regional arrangements — a system of ‘syndicated regionalism’ (Regionalism Inc.) that would fill the voids in regional economic cooperation.

The process of coordination could be institutionalized via greater cooperation among the respective development banks and other institutions, with the roadmap for greater coordination in the regional sphere spanning the likes of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRI in Eurasia, as well as similar regional/continental syndicates in Africa and Latin America.

It could further include a transcontinental element in global governance in the form of BRICS+ and a North–South cooperation mechanism that brings together the largest regional integration groupings.

Rebuilding global governance architecture with regional blocks may serve to strengthen the ‘supporting structures’ of the edifice of the global economy — with hardly any attention paid to coordination among regional arrangements, as most of the coordination and regulation was focused on the nation-state level, or the level of global institutions.

A globalization process that is based on integration and cooperation among regional blocks may harbour the advantage of being more sustainable and inclusive compared to the core–periphery paradigm of the preceding decades.

Most importantly, ‘syndicated regionalism’ offers the possibility of additional lines of communication, economic cooperation and crisis resolution at a time when the fragilities in the global economy are transcending national borders and taking on regional dimensions (hence, IMF’s greater focus on evaluating regional economic vulnerabilities).

A coordinated approach to regionalism allows the world economy to transcend some of the country-to-country barriers to economic cooperation, exploit regional ‘economies of scale’ in advancing economic cooperation, while at the same time potentially attenuating the risks of confrontation among the competing integration projects. The latter in recent years are increasingly directed toward the formation of megaregional blocks (the race to mega-regionalism) that in turn harbour ever-greater dividends as well as greater risks.

Should we give up on global governance?

Flash back to 1995. After an eight-decades-long split, the world economy was in the process of being reunified. To manage an ever-growing degree of interdependence, the global community had initiated a process aimed at strengthening the existing international institutions and creating new ones. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) had just been brought to life, equipped with a binding dispute-resolution mechanism that would, among other things, provide an effective channel for managing China’s transition from a closed, planned economy to an open economy that plays by the rules of global markets. A new round of multilateral trade negotiations was in preparation. The Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) was being negotiated under the aegis of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The creation of a global competition system was contemplated. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) would soon be given a broader mandate to oversee cross-border capital flows. A legally binding international agreement, the Kyoto Protocol on climate change, was being negotiated, and plans were drawn for an international environment organisation that would provide a fifth pillar to the global order, alongside the WTO, the Bretton Woods institutions, and the (less effective) International Labour Organisation (ILO). There were strong hopes that the institutional architecture of globalisation was being built.

The intended message to the people was clear: globalisation — a new concept at the time — was not just about liberalising flows of goods, services and capital. It was also about establishing the rules and public institutions required to steer markets, foster cooperative behaviour on the part of governments, and manage a single global economy. Global public goods — another new concept that was loosely applied to a series of issues from biodiversity to climate and from public health to financial stability — would be taken care of through jointly agreed rules of the game. The successful Montreal Protocol on eliminating ozone-depleting gases, agreed in 1987, provided an encouraging template.

These claims were not exempt from hype. Liberalisation was real, but the strengthening of the legal and institutional architecture was only in the making. Also, there were problems with the governance of global institutions:

- To start with, Europe, the United States and Japan were not only running the show by participating in the Group of Seven (G7); they were also overrepresented on the boards of the IMF and the World Bank, and they enjoyed disproportionate influence in the other major institutions. There was a clear need to redistribute power and influence in favour of emerging and developing countries, whose weight in the world population and GDP was growing fast;

- Second, governance through sectoral institutions was potentially problematic: each one dealt with one particular field, but none was in charge of cross-sectoral issues such as trade and exchange rates, trade and labour, or trade and the environment (to name just a few). True, the United Nations was meant to provide an overall framework. But in the economic field at least, the UN system was deprived of effectiveness ;

- Third, these institutions were increasingly criticised for being undemocratic because they were accountable only to governments and not to any parliamentary body. Civil society organisations and environmental NGOs were insistently calling for a remedy to these deficiencies. The international institutions were slowly learning to give them a voice.

The way forward looked clear: liberalisation would be pursued further and globalisation would be managed by strengthening and developing a network of global institutions, each of which would take responsibility for one of the main channels of interdependence. The governance of these institutions would be reformed, so that emerging and developing countries would gradually gain power at the expense of the advanced countries. These institutions would cooperate to address cross-sectoral issues and, as a substitute for proper accountability to a non-existing global parliament, they would develop a dialogue with civil society. Some, like Rodrik (1997), doubted this could be a workable solution and highlighted a trilemma between deep integration, national autonomy and democratic governance. But there was hardly another template on offer.

Fast forward now to 2018. Despite more than a decade of discussions, the global trade negotiations launched in 2001 in Doha (known as the Doha round) have not led anywhere. The WTO is still there but on the verge of becoming wholly ineffective. After obstructing the WTO’s dispute settlement system by preventing the appointment of new members to its Appellate Body, President Trump declared on 30 August 2018 that the US would pull out of the WTO unless the organisation “shapes up”1. Negotiations over the MAI collapsed in 1998. The Kyoto Protocol was signed, but was not lastingly implemented, largely because the US decided not to ratify it. The 2009 Copenhagen conference on climate change failed to reach agreement on mandatory limits on greenhouse gas emissions and ended in dispute. Less than two years after a general, though non-quantitative and non-binding agreement was reached on the occasion of the 2015 COP21 in Paris, the US announced in June 2017 its withdrawal from it. And nobody talks of a global competition system or a global environmental organisation anymore.

Economic nationalism is on the rise. Its offensive guise, state capitalism, is a much more powerful force than anybody expected a quarter of a century ago. It is especially, but far from exclusively, strong in China where corporate champions that were expected to transform into standard public companies remain under the direct or indirect control of the government. Nearly a decade after China joined the WTO, the balance between state-led coordination and market-led coordination is not at all what it was supposed to be. Contrary to expectations, there is growing fear that the Chinese model of development is diverging from the standard market economy template (Wu, 2016). Policy instruments that China regards as development levers are seen by the US administration as instruments of economic control that distort competition and hurt US interests2.

Economic nationalism’s defensive guise, protectionism, is especially, but far from exclusively strong in the US where the Trump administration has embarked on a series of ruthless (and fairly incoherent) initiatives against its main trade partners. In trade at least, it has taken the bilateral route and disregards multilateral rules and procedures entirely. Particularly worrying is the fact that the US has used a national security clause in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) to impose tariffs on imports from its allies and partners. Countries regarded as running excessive bilateral surpluses are being commanded to reduce them without delay. China has been brutally ordered to import more, export less, cut subsidies, refrain from purchasing US technology companies, curtail investment in sensitive sectors and respect intellectual property (US Government, 2018). The very principles of multilateralism, that pillar of global governance, seem to have become a relic from a distant past. The US seems to have reverted to its interwar defiance vis-à-vis the international system.

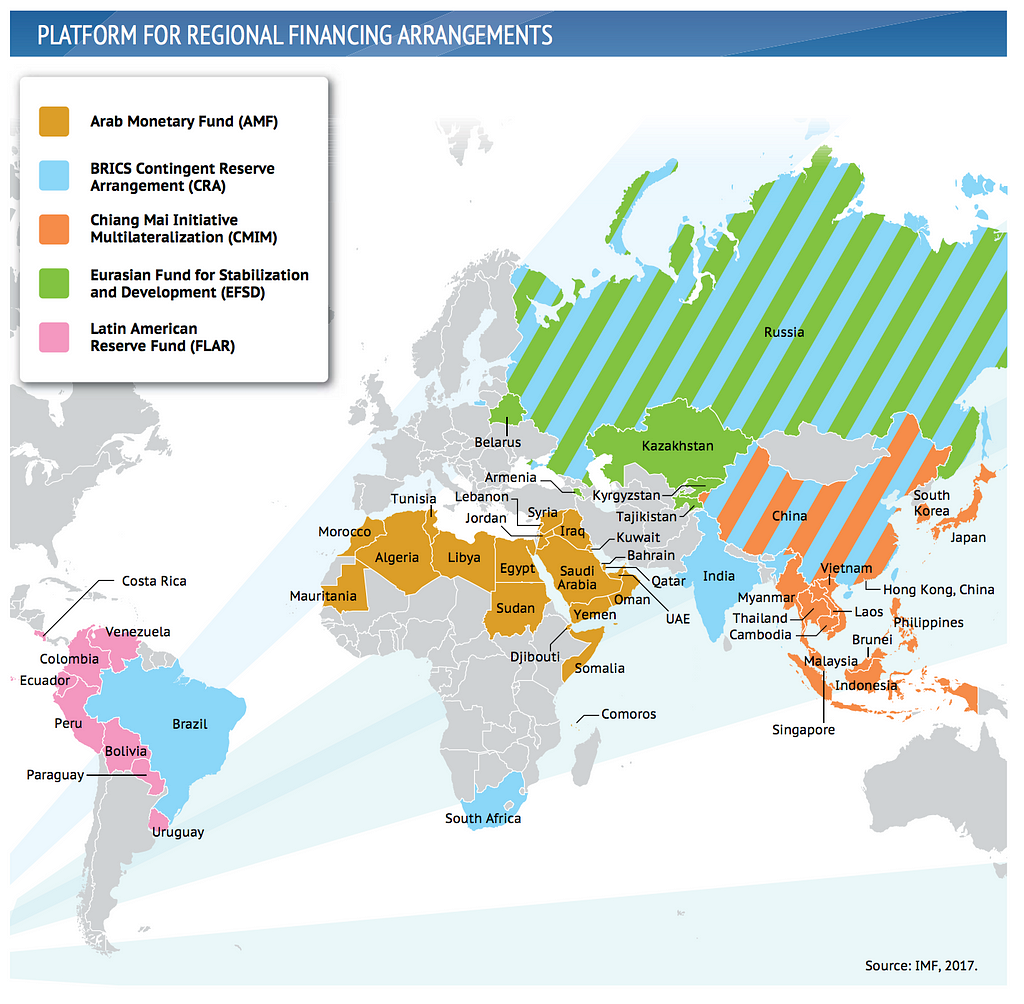

The retreat of multilateralism is not limited to the trade realm. It is also visible — though much less pronounced — in international finance where three broad trends are noticeable (De Gregorio et al, 2018). First, the IMF’s attempt to gain a formal extension of its mandate failed already in 1997 and there has been a move away from across-the-board financial account liberalisation. According to the index built by Fernández et al (2016), average restrictions on financial flows bottomed out in the mid-2000s. Since then, capital controls and other regulatory impediments to free movement of capital have regularly increased. Second, since the Asian crisis of 1998, there has been an increasing reliance on unilateral, bilateral or regional solutions rather than on the multilateral safety nets provided by the IMF. National reserves have increased more than tenfold since 2000, against a factor of 3.7 for IMF resources (Truman, 2018). In 2007–08, US dollar swap lines were extended on a strictly bilateral basis by the Federal Reserve to selected central banks; they proved instrumental in avoiding financial disruption but the initial choice of partner central banks and the later decision to grant to some of them permanent access to dollar liquidity have been purely discretionary. Third, regional financing arrangements have developed as a complement but also a potential substitute to the multilateral safety net. Whereas Europe is admittedly a special case because of the introduction of a common currency, the instruments in place could conceivably be used in a broader regional context. Reliance on regional cooperation has also developed in Asia and Latin America.

The trend is similar in relation to the environment. Although the Paris Agreement of December 2015 was hailed as a success of international cooperation, it is far less constraining than the Montreal and Kyoto protocols. Signatories did not commit to internationally determined emission ceilings nor did they subscribe to a multilateral system of rules; rather, each state individually announced what it intended to contribute to the common endeavour, frequently conditional on efforts made by others or on the availability of financial support (Tagliapietra, 2018). There is no enforcement mechanism either. Beyond climate, the failure to address the rapid deterioration of biodiversity illustrates the limits of commitments to collective action to protect the environment.

Cross-sectoral initiatives also cast doubts over the global governance model of the late twentieth century. A puzzling case is the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). At one level it can be analysed as a regional infrastructure development endeavour. But it is also presented by Chinese sponsors as a potentially more encompassing project and a “new globalisation mechanism” (Jin, 2018). US critics regard it instead as “debt diplomacy to expand influence” (Pence, 2018). An early test will be provided by the treatment of the bilateral debt overhangs of partner countries. So far, China has been reluctant to contemplate settling overindebtedness cases within the framework of the Paris Club, the usual multilateral venue.

It is hard not to conclude that recent developments in a wide range of fields have dashed the expectations of the 1990s. These developments challenge the system of universal, multilateral, public, treaty-based, institution-supported and legally enforceable rules that provided the basis for global governance since the second world war. The legal and institutional order that underpinned international economic relations for seven decades is undergoing a slow, but major overhaul.

The exception to this trend — admittedly quite a significant one, at first sight at least — has been the creation of the Group of Twenty (G20). At the end of 2008, in response to the Global Financial Crisis, the dramatic decision to establish it (or, more precisely, to elevate an existing finance ministers’ body to government leaders’ level) suddenly gave emerging countries the voice at the high table they had for many years been asking for. Furthermore, it involved them in the design of a financial and macroeconomic response to the worst crisis in six decades. In Washington in November 2008, the G20 initiated a comprehensive financial reform agenda, the implementation of which would be monitored by a new institution, the Financial Stability Board (FSB)3. In London in April 2009, the G20 engineered a concerted budgetary stimulus of an unprecedented magnitude — in which, for the first time ever, the emerging and developing countries participated alongside the advanced countries. In London also, it was decided to increase significantly the resources of the IMF and to proceed with a special one-time allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), in order to beef up liquidity at the global level. And in Pittsburgh in September 2009, the G20 initiated a Mutual Assessment Process through which the contribution of national policies to the reduction of global imbalances would be regularly monitored by the IMF and discussed among national policymakers4. Since then, the G20 has continued to serve as platform for political dialogue and as a steering body for collective initiatives in a variety of fields (Bery, 2018).